چین میں مذہب

حکومت عوامی جمہوریہ چین نے مذہب کے معاملے میں ریاستی الحاد کا اعلان کر رکھا ہے۔ تاہم چینی تمدن تاریخی طور پر طویل عرصے سے دنیا میں مذہبی-فلسفہ روایات کے لیے ایک اہم میزبان رہا ہے اور کئی مذاہب یہیں سے پروان چڑھے ہیں۔ کنفیوشس مت اور تاؤ مت، بعد میں بدھ مت نے بھی اس میں شمولیت اختیار کی "تعلیمات ثلاثہ" پر مشتمل ہیں جنھوں نے چینی ثقافت کی تشکیل کی ہے۔ اس متغیر مذہبی نظام کے درمیان کوئی واضح حدود نہیں ہیں، جو خاص ہونے کا دعوی نہیں کرتا ہے اور ہر ایک کے عناصر مقبول لوک مذہب کو فروغ دیتے ہیں۔ شہنشاہان چین نے بہشتی تولیت (Mandate of Heaven) کے حق کا دعوی کیا اور چینی مذہبی رسومات میں حصہ لیا۔ بیسویں صدی کے آغاز میں اصلاحات پسند افسران اور دانشوروں نے تمام مذاہب پر "غیر معمولی" ہونے کا الزام لگایا اور 1949ء کے بعد سے عوامی جمہوریہ چین میں چینی کمیونسٹ پارٹی کی حکومت ہے جو ایک ملحد ادارہ ہے جس میں پارٹی کے ارکان کو دفتر میں کسی قسم کی مذہبی رسوم ادا کرنے سے روکتا ہے۔ انیسویں صدی کے اواخر سے الحادی اور مذہب مخالف مہمات کا ایک سلسلہ جاری ہے، پرانے عادات، خیالات، رواج اور ثقافت کے خلاف ثقافتی انقلاب جو 1966ء سے 1967ء تک چلا نے مذہبی قوتوں کو تباہ کر دیا یا ان کو زیر زمین ہونے پر مجبور کر دیا۔[3][4] بعد میں آنے والے رہنماؤں نے مذہبی تنظیموں کو زیادہ خود مختاری دی۔ سرکاری طور پر حکومت پانچ مذاہب کو تسلیم کرتی ہے جو بدھ مت، تاؤ مت، کاتھولک مسیحیت (چینی کاتھولک کلیسیا رومی کاتھولک کلیسیا سے آزاد ہے)، پروٹسٹنٹ مسیحیت اور اسلام ہیں۔ بیسویں صدی کے آغاز میں کنفیوشس مت اور چینی لوک مذہب کو چین کی ثقافتی وراثے کا حصے کے طور پر سرکاری طور پر تسلیم کرنے میں اضافہ ہوا ہے۔

لوک یا مقبول مذہب اور ان کے عقائد اور طریقوں کا وسیع پیمانے پر نظام کا آغاز شانگ دور اور ژؤ دور میں ہوا۔ مسیحیت اور اسلام جین میں ساتویں صدی میں آئے۔ چین کو اکثر انسان دوستی اور سیکولرازم کا ایک گھر سمجھا جاتا ہے جس کا آغاز کنفیوشس دور سے ہوا۔

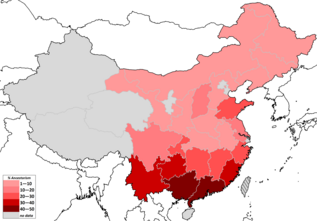

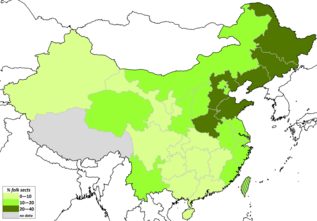

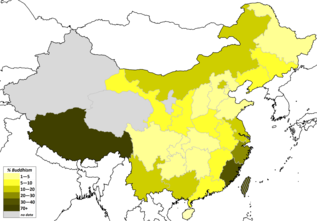

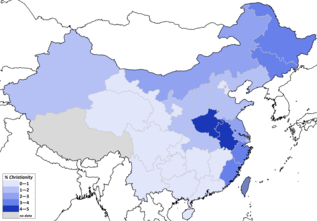

مذاہب بلحاظ صوبہ

[ترمیم]| صوبہ | چینی اجداد پرستی[5] |

بدھ مت[13] | مسیحیت[13] | اسلام[14] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| فوجیان | 31.31% | 40.40% | 3.97% | 0.32% |

| ژجیانگ | 23.02% | 23.99% | 3.89% | <0.2% |

| گوانگشی | 40.48% | 10.23% | 0.15% | <0.2% |

| گوانگڈونگ | 43.71% | 5.18% | 0.68% | <0.2% |

| یوننان | 32.22% | 13.06% | 0.68% | 1.52% |

| گوئیژو | 31.18% | 1.86% | 0.49% | 0.48% |

| جیانگسو | 16.67% | 14.17% | 2.67% | <0.2% |

| جیانگشی | 24.05% | 7.96% | 0.66% | <0.2% |

| شانڈونگ | 25.28% | 2.90% | 1.54% | 0.55% |

| چونگ چنگ | 26.63% | 0.85% | 0.28% | <0.2% |

| ہونان | 20.19% | 2.44% | 0.49% | <0.2% |

| شنسی | 15.61% | 3.65% | 1.55% | <0.2% |

| ہینان | 7.94% | 5.52% | 4.95% | 1.05% |

| جیلن | 7.73% | 8.23% | 3.26% | <0.2% |

| انہوئی | 4.64% | 7.83% | 4.32% | 0.58% |

| گانسو | 3.51% | 6.85% | 0.28% | 6.64% |

| ہیلونگجیانگ | 7.73% | 4.39% | 3.63% | 0.35% |

| شانسی | 7.58% | 6.35% | 1.66% | 0.4% |

| لیاؤننگ | 7.73% | 5.31% | 1.99% | 0.64% |

| سیچوان | 10.6% | 2.06% | 0.30% | <0.2% |

| ہوبئی | 6.5% | 2.09% | 1.71% | <0.2% |

| ہیبئی | 5.52% | 1.59% | 1.13% | 0.82% |

| ہائنان | – | – | 0.48%[5] | <0.2% |

| بیجنگ | – | 11.2%[16] | 0.78%[5] | 1.76% |

| شنگھائی | – | 10.30% | 1.88% | 0.36% |

| تیانجن | – | – | 0.43% | <0.2% |

| تبت | – | ~78%[17] | – | 0.39% |

| سنکیانگ | – | – | 1.0%[5] | 57.99% |

| نینگشیا | – | – | 1.17%[5] | 33.99% |

| چنگھائی | – | – | 0.76%[5] | 17.51% |

| اندرونی منگولیا | 2.36% | 12.1%[18] | 2.0%[5] | 0.91% |

| چین | 16%[19] | 15%[2] | 2.5%[2] | 2%[15]:13 |

مزید دیکھیے

[ترمیم]- دیگر

- چین میں مسیحیت

- چین میں اسلام

- اندرونی منگولیا میں مذہب

- ہانگ کانگ میں مذہب

- مکاؤ میں مذہب

- شمال مشرقی چین میں مذہب

- تائیوان میں مذہب

حواشی

[ترمیم]- ↑ CFPS 2014 surveyed a sample of 13,857 families and 31,665 individuals.[2]:27, note 4 As noted by Katharina Wenzel-Teuber of China Zentrum, German institute for research on religion in China, compared to CFPS 2012, CFPS 2014 asked the Chinese about personal belief in certain conceptions of divinity (i.e. "Buddha"، "Tao"، "God of the Christians/Jesus"، "Heavenly Lord of the Catholics") rather than membership in a religious group.[2]:27 It also included regions, such as those in the west of China, that were excluded in CFPS 2012,[2]:27, note 3 and unregistered Christians.[2]:28 For these reasons, she concludes that CFPS 2014 results are more accurate than 2012 ones.

- ↑ CFPS 2017 found that 5.94% of the population declared that they belonged to "other" religious categories besides the five state-sanctioned religions. An additional 0.85% of the population responded that they were "Taoists"۔ Note that the title of "Taoist"، in common Chinese usage, is generally attributed only to the Taoist clergy۔ CFPS 2014 found that a further 0.81% declared that they belonged to the popular salvationist sects, while CFPS 2012 found 2.2%، and CGSS 2006–2010 surveys found an average 3% of the population declaring that they belonged to such religions, while government estimates give higher figures (see the "statistics" section of the present article)۔

- ↑ CFPS 2014 surveyed predominantly people of ہان چینی۔ This may have resulted in an underestimation of Muslims. CGSS 2006–2010 surveys found an average 2-3% of the population of China declaring to be Muslim.

- ↑ Chinese ancestral or lineage religion is the worship of kin's ancestor-gods in the system of lineage churches and ancestral shrines. It is worthwhile to note that this does not include other forms of Chinese religion, such as the worship of national ancestral gods or the gods of nature (which in northern China is more common than ancestor worship)، and Taoism and Confucianism.

- ↑ The map represents the geographic diffusion of the tradition of folk religious movements of salvation, Confucian churches and jiaohua ("transformative teachings") movements, based on historical data and contemporary fieldwork. Due to incomplete data and ambiguous identity of many of these traditions the map may not be completely accurate. Sources include a World Religion Map from Harvard University, based on data from the World Religion Database, showing highly unprecise ranges of Chinese folk (salvationist) religions' membership by province. Another source, the studies of China's Regional Religious System، find "very high activity of popular religion and secret societies and low Buddhist presence in northern regions, while very high Buddhist presence in the southeast"۔[6]

Historical record and contemporary scholarly fieldwork testify certain central and northern provinces of China as hotbeds of folk religious sects and Confucian religious groups.

- ہیبئی: Fieldwork by Thomas David Dubois[7] testifies the dominance of folk religious movements, specifically the Church of the Heaven and the Earth and the Church of the Highest Supreme، since their "energetic revival since the 1970s" (p. 13)، in the religious life of the counties of Hebei. Religious life in rural Hebei is also characterised by a type of organisation called the benevolent churches and the salvationist movement known as Zailiism has returned active since the 1990s.

- ہینان: According to Heberer and Jakobi (2000)[8] Henan has been for centuries a hub of folk religious sects (p. 7) that constitute significant focuses of the religious life of the province. Sects present in the region include the Baguadao or Tianli ("Order of Heaven") sect, the Dadaohui, the Tianxianmiaodao، the Yiguandao، and many others. Henan also has a strong popular Confucian orientation (p. 5)۔

- شمال مشرقی چین: According to official records by the then-government, the Universal Church of the Way and its Virtue or Morality Society had 8 million members in منچوریا، or northeast China in the 1930s, making up about 25% of the total population of the area (note that the state of Manchuria also included the eastern end of modern-day Inner Mongolia)۔[9] Folk religious movements of a Confucian nature, or Confucian churches, were in fact very successful in the northeast.

- شانڈونگ: The province is traditionally a stronghold of Confucianism and is the area of origin of many folk religious sects and Confucian churches of the modern period, including the Universal Church of the Way and its Virtue, the Way of the Return to the One (皈依道 Guīyīdào)، the Way of Unity (一貫道 Yīguàndào)، and others. Alex Payette (2016) testifies the rapid growth of Confucian groups in the province in the 2010s.[10]

- ↑ The statistics for Chinese ancestorism, that is the worship of ancestor-gods within the lineage system, are from the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey of 2010.[5] The statistics for Buddhism and Christianity are from the China Family Panel Studies survey of 2012.[13] The statistics for Islam are from a survey conducted in 2010.[14] It is worthwhile to note that the populations of Chinese ancestorism and Buddhism may overlap, even with the large remaining parts of the population whose belief is not documented in the table. The latter, the uncharted population, may practise other forms of Chinese religion, such as the worship of gods, Taoism, Confucianism and folk salvationisms, or may be atheist. Indeed, according to the CFPS 2012, only 6.3% of the Chinese were irreligious in the sense of "atheism"، while the rest practised the worship of gods and ancestors.[15]:13

حوالہ جات

[ترمیم]- ↑ For China Family Panel Studies 2017ء survey results see release #1 (archived) and release #2 (archived)۔ The tables also contain the results of CFPS 2012 (sample 20,035) and Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) results for 2006, 2008 and 2010 (samples ~10.000/11,000)۔ Also see, for comparison CFPS 2012 data in Yunfeng 云峰 Lu 卢 (2014)۔ "卢云峰:当代中国宗教状况报告——基于CFPS(2012)调查数据" [Report on Religions in Contemporary China – Based on CFPS (2012) Survey Data] (PDF)۔ World Religious Cultures (1)۔ 9 اگست 2014 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ p. 13, reporting the results of the CGSS 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2011, and their average (fifth column of the first table)۔

- ^ ا ب پ ت ٹ ث ج Katharina Wenzel-Teuber۔ "Statistics on Religions and Churches in the People's Republic of China – Update for the Year 2016" (PDF)۔ Religions & Christianity in Today's China۔ VII (2)۔ صفحہ: 26–53۔ 22 جولائی 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ

- ↑ Sa'eda Buang، Phyllis Ghim-Lian Chew (9 May 2014)۔ Muslim Education in the 21st Century: Asian Perspectives (بزبان انگریزی)۔ Routledge۔ صفحہ: 75۔ ISBN 978-1-317-81500-6۔

Subsequently, a new China was found on the basis of Communist ideology, i.e. atheism. Within the framework of this ideology, religion was treated as a 'contorted' world-view and people believed that religion would necessarily disappear at the end, along with the development of human society. A series of anti-religious campaigns was implemented by the Chinese Communist Party from the early 1950s to the late 1970s. As a result, in nearly 30 years between the beginning of the 1950s and the end of the 1970s, mosques (as well as churches and Chinese temples) were shut down and Imams involved in forced 're-education'.

- ↑ Linda Woodhead، Hiroko Kawanami، Christopher H. Partridge، مدیران (2009)۔ Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations (2nd ایڈیشن)۔ London: Routledge۔ ISBN 0415458900۔ OCLC 237880815

- ^ ا ب پ ت ٹ ث ج چ ح Data from the Chinese Spiritual Life Survey (CSLS) 2010 for Chinese ancestorists, and from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) 2009 for Christians. Reported in Xiuhua Wang (2015)۔ "Explaining Christianity in China: Why a Foreign Religion has Taken Root in Unfertile Ground" (PDF)۔ Baylor University۔ صفحہ: 15۔ 25 ستمبر 2015 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ

- ↑ Jiang Wu، Daoqin Tong۔ "Spatial Analysis and GIS Modeling of Regional Religious Systems in China" (PDF)۔ University of Arizona۔ 27 اپریل 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ

- ↑ Dubois (2005).

- ↑ Thomas Heberer، Sabine Jakobi (2000)۔ "Henan – The Model: From Hegemonism to Fragmentism. Portrait of the Political Culture of China's Most Populated Province" (PDF)۔ Duisburg Working Papers on East Asian Studies (32)۔ 19 جنوری 2021 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- ↑ Ownby (2008).

- ↑ Payette (2016).

- ↑ Yunfeng 云峰 Lu 卢 (2014)۔ "卢云峰:当代中国宗教状况报告——基于CFPS(2012)调查数据" [Report on Religions in Contemporary China – Based on CFPS (2012) Survey Data] (PDF)۔ World Religious Cultures (1)۔ 9 اگست 2014 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ p. 13. The report compares the data of the China Family Panel Studies 2012 with those of the Renmin University's Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) of the years 2006, 2008, 2010 and 2011.

- ↑ لوا خطا ماڈیول:Citation/CS1 میں 4492 سطر پر: attempt to index field 'url_skip' (a nil value)۔ The map illustrates local religion led by Taoist specialists, forms and institutions.

- ^ ا ب پ ت ٹ Data from the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) 2012. Reported in Rong Hua Gai، Jun Hui Gao (22 دسمبر 2016)۔ "Multiple-Perspective Analysis on the Geological Distribution of Christians in China"۔ PEOPLE: International Journal of Social Sciences۔ 2 (1)۔ صفحہ: 809–817۔ ISSN 2454-5899۔ doi:10.20319/pijss.2016.s21.809817

- ^ ا ب پ Data from Zongde Yang (2010)۔ "Study on Current Muslim Population in China" (PDF)۔ Jinan Muslim (2)۔ 27 اپریل 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ Reported in Junqing Min (2013)۔ "The Present Situation and Characteristics of Contemporary Islam in China" (PDF)۔ JISMOR (8)۔ 24 جون 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ p. 29.

- ^ ا ب

- ↑ Hongyi Lai (2016)۔ China's Governance Model: Flexibility and Durability of Pragmatic Authoritarianism۔ Routledge۔ ISBN 978-1-317-85952-9 p. 167.

- ↑ "Internazional Religious Freedom Report 2012" (PDF)۔ US Government p. 20, quoting: "Most ethnic Tibetans practice Tibetan Buddhism, although a sizeable minority practices Bon, an indigenous religion, and very small minorities practice Islam, Catholicism, or Protestantism. Some scholars estimate that there are as many as 400,000 Bon followers across the Tibetan Plateau. Scholars also estimate that there are up to 5,000 ethnic Tibetan Muslims and 700 ethnic Tibetan Catholics in the TAR"۔

- ↑ Jiayu Wu، Yong Fang (جنوری 2016)۔ "Study on the Protection of the Lama Temple Heritage in Inner Mongolia as a Cultural Landscape"۔ Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering۔ 15 (1)۔ 24 ستمبر 2017 میں اصل سے آرکائیو شدہ Note that the article, in an evident mistranslation from Chinese, reports 30 million Tibetan Buddhists in Inner Mongolia instead of 3 million.

- ↑

ماخذ

[ترمیم]- Joseph A. Adler (2005)، "Chinese Religion: An Overview"، $1 میں Lindsay Jones، Encyclopedia of Religion (2nd ایڈیشن)، Detroit: Macmillan Reference USA۔ Available at the author's website: Joseph Adler Department of Religious Studies, کینین کالج۔

- Joseph A. Adler (2014)، Confucianism as a Religious Tradition: Linguistic and Methodological Problems (PDF)، Gambier, Ohio, USA: Kenyon College۔

- لوا خطا ماڈیول:Citation/CS1 میں 4492 سطر پر: attempt to index field 'url_skip' (a nil value)۔

- Daniel H. Bays (2012)۔ A New History of Christianity in China۔ Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell۔ ISBN 978-1-4051-5954-8

- Sébastien Billioud (2010)۔ "Carrying the Confucian Torch to the Masses: The Challenge of Structuring the Confucian Revival in the People's Republic of China" (PDF)۔ OE۔ 49

- Sébastien Billioud، Joël Thoraval (2015)۔ The Sage and the People: The Confucian Revival in China۔ Oxford University Press۔ ISBN 0-19-025814-4

- Kim-Kwong Chan (2005)۔ "Religion in China in the Twenty-first Century: Some Scenarios"۔ Religion, State & Society۔ 33 (2)۔ doi:10.1080/09637490500118570

- Ruth H. Chang (2000)۔ "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang Dynasties" (PDF)۔ Sino-Platonic Papers۔ Victor H. Mair (108)۔ ISSN 2157-9679

- Adam Yuet Chau (2005)۔ Miraculous Response: Doing Popular Religion in Contemporary China۔ ISBN 978-0-8047-5160-5

- Yong Chen (2012)۔ Confucianism as Religion: Controversies and Consequences۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9004243739

- Julia Ching (1993)۔ Chinese Religions۔ Houndsmills; London: Macmillan۔ ISBN 978-0-333-53174-7 Various reprints.

- Philip Clart (2014)، "Conceptualizations of "Popular Religion" in Recent Research in the People's Republic of China" (PDF)، $1 میں Chien-chuan Wang، Shiwei Li، Yingfa Hong، Yanjiu xin shijie: "Mazu yu Huaren minjian xinyang" guoji yantaohui lunwenji (PDF)، Taipei: Boyang، صفحہ: 391–412، ISBN 978-0-19-959653-9

- Philip Clart (2003)۔ "Confucius and the Mediums: Is There a "Popular Confucianism"?" (PDF)۔ T'oung Pao۔ Leiden: Brill۔ LXXXIX

- Edward Craig (1998)، Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy، 7، Taylor & Francis، ISBN 978-0-415-07310-3

- J.J.M. De Groot (1892)۔ The Religious System of China: Its Ancient Forms, Evolution, History and Present Aspect, Manners, Customs and Social Institutions Connected Therewith۔ Leiden, Netherlands: Brill 6 volumes. Online: Les classiques des sciences sociales, Université du Québec à Chicoutimi; Scribd: Vol. 1، Vol. 2، Vol. 3، Vol. 4، Vol. 5، Vol. 6۔

- John C. Didier (2009)۔ "In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200"۔ Sino-Platonic Papers۔ Victor H. Mair (192) Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot، Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China، Volume III: Terrestrial and Celestial Transformations in Zhou and Early-Imperial China۔

- Thien Do (2003)۔ Vietnamese Supernaturalism: Views from the Southern Region۔ Anthropology of Asia۔ Routledge۔ ISBN 0-415-30799-6

- Thomas David Dubois (2005)۔ The Sacred Village: Social Change and Religious Life in Rural North China (PDF)۔ University of Hawaii Press۔ ISBN 0-8248-2837-2۔ 10 جنوری 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- Grégoire Espesset (2008)، "Latter Han Mass Religious Movements and the Early Daoist Church"، $1 میں John Lagerwey، Marc Kalinowski، Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD)، Early Chinese Religion، Leiden: Brill، صفحہ: 1117–1158، ISBN 9004168354۔ Consulted HAL-SHS version، pages 1–56.

- Lizhu Fan، Na Chen (2015a)، "Revival of Confucianism and Reconstruction of Chinese Identity"، The Presence and Future of Humanity in the Cosmos، Tokyo, 18–23 مارچ: ICU

- Lizhu Fan، Na Chen (2013)۔ "The Revival of Indigenous Religion in China" (PDF)۔ China Watch۔ Fudan University، Fudan-UC Center for China Studies۔ doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195338522.013.024 Preprint from The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion، 2014.

- Lizhu Fan، Na Chen (2015)۔ "The Religiousness of "Confucianism" and the Revival of Confucian Religion in China Today"۔ Cultural Diversity in China۔ De Gruyter Open (1): 27–43۔ ISSN 2353-7795۔ doi:10.1515/cdc-2015-0005

- Herbert Fingarette (1972)۔ Confucius: The Secular as Sacred۔ New York City: Harper

- Stephan Feuchtwang (2016)، "Chinese religions"، $1 میں Linda Woodhead، Hiroko Kawanami، Christopher H. Partridge، Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations (3nd ایڈیشن)، London: Routledge، صفحہ: 143–172، ISBN 1-317-43960-0۔

- Jeanine D. Fowler (2005)۔ An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism: Pathways to Immortality۔ Sussex Academic Press۔ ISBN 1-84519-086-6[مردہ ربط]

- Yiu-ming Fung (2008)، "Problematizing Contemporary Confucianism in East Asia"، $1 میں Jeffrey Richey، Teaching Confucianism، Oxford University Press، ISBN 0-19-804256-6۔

- Monika Gaenssbauer (2015)۔ Popular Belief in Contemporary China: A Discourse Analysis۔ Projekt Verlag۔ ISBN 0-226-30416-7

- Vincent Goossaert، David Palmer (2011)۔ The Religious Question in Modern China۔ University of Chicago Press۔ ISBN 0-226-30416-7

- Jun Jing (1996)۔ The Temple of Memories: History, Power, and Morality in a Chinese Village۔ Stanford University Press۔ ISBN 0-8047-2756-2

- Ian Johnson (2017)۔ The Souls of China: The Return of Religion after Mao۔ New York: Pantheon Books۔ ISBN 978-1-101-87005-1

- Yaning Kao (2014)۔ "Religious Revival among the Zhuang People in China: Practising "Superstition" and Standardizing a Zhuang Religion"۔ Journal of Current Chinese Affairs۔ 43 (2): 107–144۔ ISSN 2353-7795 آئی ایس ایس این 1868-4874 (online)، آئی ایس ایس این 1868-1026 (print)۔

- David N. Keightley (2004)، "The Making of the Ancestors: Late Shang Religion and Its Legacy"، $1 میں John Lagerwey، Religion and Chinese Society، 1، Shatin: Chinese University Press، صفحہ: 3–63، ISBN 9629961237

- Olivia Kraef (2014)۔ "Of Canons and Commodities: The Cultural Predicaments of Nuosu-Yi "Bimo Culture""۔ Journal of Current Chinese Affairs۔ 43 (2): 145–179

- John Lagerwey (2010)۔ China: A Religious State۔ Hong Kong: University of Hong Kong Press۔ ISBN 9888028049

- John Lagerwey، Marc Kalinowski (2008)۔ Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD)۔ Early Chinese Religion۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9004168354

- John Lagerwey، Pengzhi Lü (2009)۔ Early Chinese Religion, Part Two: The Period of Division (220-589 AD)۔ Early Chinese Religion۔ Brill۔ ISBN 904742929X

- John Lagerwey، Pierre Marsone (2014)۔ Modern Chinese Religion I: Song-Liao-Jin-Yuan (960-1368 AD)۔ Modern Chinese Religion۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9004271643

- John Lagerwey، Vincent Goossaert، Jan Kiely (2015)۔ Modern Chinese Religion II: 1850–2015۔ Modern Chinese Religion۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9004304649

- André Laliberté (2011)۔ "Religion and the State in China: The Limits of Institutionalization"۔ Journal of Current Chinese Affairs۔ 40 (2): 3–15

- Pui-Lam Law (2005)۔ "The Revival of Folk Religion and Gender Relationships in Rural China: A Preliminary Observation"۔ Asian Folklore Studies۔ 64: 89–109[مردہ ربط]

- Ulrich Libbrecht (2007)۔ Within the Four Seas.۔۔: Introduction to Comparative Philosophy۔ Peeters Publishers۔ ISBN 9042918128

- Ronnie Littlejohn (2010)۔ Confucianism: An Introduction۔ I. B. Tauris۔ ISBN 1-84885-174-X

- Daji Lü، Xuezeng Gong (2014)۔ Marxism and Religion۔ Religious Studies in Contemporary China۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9047428021

- Richard Madsen (2010)۔ "The Upsurge of Religion in China" (PDF)۔ Journal of Democracy۔ 21 (4): 58–71۔ 14 جولائی 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- James Miller (2006)۔ Chinese Religions in Contemporary Societies۔ ABC-CLIO۔ ISBN 1-85109-626-4

- Randal L. Nadeau (2012)۔ The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions۔ Malden, MA: Blackwell

- Daniel L. Overmyer (2009)۔ Local Religion in North China in the Twentieth Century the Structure and Organization of Community Rituals and Beliefs (PDF)۔ Leiden; Boston: Brill۔ ISBN 9789047429364[مردہ ربط]

- Daniel L. Overmyer (1986)۔ Religions of China: The World as a Living System۔ New York: Harper & Row

- Daniel Overmyer (2003)۔ Religion in China Today۔ Cambridge University Press۔ ISBN 0-521-53823-8

- David Ownby (2008)۔ "Sect and Secularism in Reading the Modern Chinese Religious Experience"۔ Archives de sciences sociales des religions۔ 144۔ doi:10.4000/assr.17633

- David A. Palmer، Glenn L. Shive، Philip L. Wickeri (2011)۔ Chinese Religious Life۔ Oxford University Press۔ ISBN 0-19-973138-1

- David A. Palmer (2011)۔ "Chinese Redemptive Societies and Salvationist Religion: Historical Phenomenon or Sociological Category?" (PDF)۔ Journal of Chinese Ritual, Theatre and Folklore۔ 172: 21–72

- David W. Pankenier (2013)۔ Astrology and Cosmology in Early China۔ Cambridge University Press۔ ISBN 1-107-00672-4

- Julian F. Pas (1998)۔ Historical Dictionary of Taoism۔ Historical Dictionaries of Religions, Philosophies, and Movements Series۔ Scarecrow Press۔ ISBN 0-8108-6637-4

- Alex Payette (فروری 2016)۔ "Local Confucian Revival in China: Ritual Teachings, 'Confucian' Learning and Cultural Resistance in Shandong"۔ China Report۔ 52 (1): 1–18۔ doi:10.1177/0009445515613867 [مردہ ربط]

- Alex Payette (2014)، "Shenzhen's Kongshengtang: Religious Confucianism and Local Moral Governance"، Panel RC43: Role of Religion in Political Life (PDF)، 23rd World Congress of Political Science, 19–24 جولائی، 23 اکتوبر 2017 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ، اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- Fabrizio Pregadio (2013)۔ The Encyclopedia of Taoism۔ Routledge۔ ISBN 1-135-79634-3 Two volumes: 1) A-L; 2) L-Z.

- Fabrizio Pregadio (2016)۔ "Religious Daoism"۔ $1 میں Edward N. Zalta۔ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2016 ایڈیشن)۔ Stanford University

- Miikka Ruokanen، Paulos Zhanzhu Huang، مدیران (2011)، Christianity and Chinese Culture، William B. Eerdmans Publishing، ISBN 0-8028-6556-9

- Jeffrey Riegel (Summer 2013)۔ "Confucius"۔ $1 میں Edward N. Zalta۔ The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Barry Sautman (1997)، "Myths of Descent, Racial Nationalism and Ethnic Minorities in the People's Republic of China"، $1 میں Frank Dikötter، The Construction of Racial Identities in China and Japan: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives، Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press، صفحہ: 75–95، ISBN 9622094430

- Meir Shahar، Robert Paul Weller (1996)۔ Unruly Gods: Divinity and Society in China۔ University of Hawaii Press۔ ISBN 0-8248-1724-9

- Qingsong Shen، Kwong-loi Shun (2007)۔ Confucian Ethics in Retrospect and Prospect۔ Council for Research in Values & Philosophy۔ ISBN 1-56518-245-6

- Yilong 石奕龍 Shi (2008)۔ "中国汉人自发的宗教实践 – 神仙教 (Zhongguo Hanren zifadi zongjiao shijian: Shenxianjiao)" [The Spontaneous Religious Practices of Han Chinese Peoples – Shenxianism]۔ 中南民族大学学报 — 人文社会科学版 (Journal of South-Central University for Nationalities – Humanities and Social Sciences)۔ 28 (3): 146–150۔ 31 اگست 2019 میں اصل سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- Wei Leong Tay (2010)۔ "Kang Youwei: The Martin Luther of Confucianism and His Vision of Confucian Modernity and Nation" (PDF)۔ Secularization, Religion and the State۔ University of Tokyo Center of Philosophy

- Stephen F. Teiser (1988)۔ The Ghost Festival in Medieval China۔ Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press۔ ISBN 0-691-05525-4

- Stephen F. Teiser (1996)، "The Spirits of Chinese Religion" (PDF)، $1 میں Donald S. Lopez Jr.، Religions of China in Practice (PDF)، Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press۔ Extracts in The Chinese Cosmos: Basic Concepts۔

- Stephen F. Teiser (1995)۔ "Popular Religion"۔ Journal of Asian Studies۔ 54 (2): 378–395۔ doi:10.2307/2058743

- Arthur Waldron (1998)۔ "Religious Revivals in Communist China"۔ Orbis۔ 42 (2): 325–334

- Zhibin Xie (2006)۔ Religious Diversity and Public Religion in China۔ Ashgate Publishing۔ ISBN 978-0-7546-5648-7

- Fenggang Yang، Graeme Lang (2012)۔ Social Scientific Studies of Religion in China۔ Brill۔ ISBN 9004182462

- C.K. Yang (1961)۔ Religion in Chinese Society: A Study of Contemporary Social Functions of Religion and Some of Their Historical Factors۔ Berkeley: University of California Press۔ ISBN 0-520-01371-9

- Mayfair Mei-hui Yang (2007)۔ "Ritual Economy and Rural Capitalism with Chinese Characteristics" (PDF)۔ $1 میں David Held، Henrietta Moore۔ Cultural Politics in a Global Age: Uncertainty, Solidarity and Innovation (PDF)۔ Oxford: Oneworld Publications۔ ISBN 1-85168-550-2۔ 03 مارچ 2016 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- Fenggang Yang، Anning Hu (2012)۔ "Mapping Chinese Folk Religion in Mainland China and Taiwan"۔ Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion۔ 51 (3): 505–521۔ doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2012.01660.x

- Xinzhong Yao (2010)۔ Chinese Religion: A Contextual Approach۔ London: A&C Black۔ ISBN 978-1-84706-475-2

- Xinzi Zhong (2014)۔ A Reconstruction of Zhū Xī's Religious Philosophy Inspired by Leibniz: The Natural Theology of Heaven (مقالہ)۔ Open Access Theses and Dissertations۔ Hong Kong Baptist University Institutional Repository۔ 09 جون 2019 میں اصل (PDF) سے آرکائیو شدہ۔ اخذ شدہ بتاریخ 18 مارچ 2019

- Jixu Zhou (2005)۔ "Old Chinese "*tees" and Proto-Indo-European "*deus": Similarity in Religious Ideas and a Common Source in Linguistics" (PDF)۔ Sino-Platonic Papers۔ Victor H. Mair (167)

- Youguang Zhou (2012)۔ "To Inherit the Ancient Teachings of Confucius and Mencius and Establish Modern Confucianism" (PDF)۔ Sino-Platonic Papers۔ Victor H. Mair (226)

مزید پڑھیے

[ترمیم]- Kenneth K. S. Ch'en (1972)۔ Buddhism in China, a Historical Survey۔ Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press۔ ISBN 0-691-00015-8

- Jordan D. Paper (1995)۔ The Spirits are Drunk: Comparative Approaches to Chinese Religion۔ Albany, NY: State University of New York Press۔ ISBN 0-7914-2315-8

- Arthur F. Wright (1959)۔ Buddhism in Chinese History۔ Stanford University Press۔ ISBN 0-8047-0548-8

بیرونی روابط

[ترمیم]| ویکی ذخائر پر چین میں مذہب سے متعلق سمعی و بصری مواد ملاحظہ کریں۔ |

- Chinese Buddhist Association

- China Confucian Philosophy

- China Confucian Religionآرکائیو شدہ (Date missing) بذریعہ rjzg.net (Error: unknown archive URL)

- China Confucian Templesآرکائیو شدہ (Date missing) بذریعہ chinakongmiao.org (Error: unknown archive URL)

- Holy Confucian Church of Chinaآرکائیو شدہ (Date missing) بذریعہ zhksh.org (Error: unknown archive URL)

- Chinese Taoist Association

- Chinese Folk Temples' Management Associationآرکائیو شدہ (Date missing) بذریعہ minjiansimiao.com (Error: unknown archive URL)

تعلیمی

- Living in the Chinese Cosmos، Asia for Educators, Columbia University.

- China Zentrum، Germany-based institute for research on religion in China

میڈیا

- Euraxess Science Slam: Meihuaquan and Community Life in North China

- eRenlai Ricci: The boundary between religion and the state in China by Prof. Lagerwey

- GBTimes: THE DEBATE: Insight into religion in modern China (part 1)—Part 2

- Berkeley Center: Ritual Economy and Religious Revivial in Rural Southeast China

- Berkeley Center: Secularization Theory and the Study of Chinese Religions

- Berkeley Center: Understanding Contemporary Religious Pluralism in China